Harold Cornwell - Apprentice Surveyor, Rifleman, Merchant Navy Wireless Officer

53949 Rifleman Harold Frederick Francis Cornwell, 8th (Leeds Rifles) Battalion

The way the British Army inducted and trained its new soldiers changed remarkably during the Great War. While it remained possible for men to volunteer for the Regular Army, following the passing of the Military Service Act of 1916 into law in Great Britain, most recruits entering the Army did so because they had been conscripted. When the war began, the army relied on men volunteering, and until the creation of temporary training camps under the New Army arrangements, infantry recruits were brought into the Army through the regimental depot system, a creature of the 1881 Childers Reforms of the Army which gave each infantry regiment a geographic affiliation and an associated recruiting district. Until that time, line infantry regiments had been numbered regiments of foot, but after the Childers Reforms regiments adopted county titles and established Headquarters and Depots within those districts.

With the dramatic rise in recruit numbers following the declaration of war in August 1914, the regimental depot system for training recruits was less able to cope with the numbers of men joining the army, with men often being billeted in the homes of local civilians. Gradually, this forced the authorities to expand into temporary camps such as those on Salisbury Plain, Cannock Chase and Clipstone Camp, near Mansfield.

Following the introduction of conscription in early 1916, the numbers of men flowing into the army could be more accurately predicted, and therefore, the army training establishments were better able to plan the training programme the men would be inducted to. This made a more standard, structured training regime necessary to provide the field army with a regular supply of trained men. The result of the standardisation was the creation of the Training Reserve in September 1916.

Apprentice surveyor Harold Frederick Francis Cornwell was called up to attest for the army on 28th February 1917, a month before his eighteenth birthday on 25th March. He was transferred to the Army Reserve to await his mobilisation notice, which came during the second week of April, and ordered him to report to Normanton Barracks in Derby, the Depot of the Sherwood Foresters on 28th April.

|

| Normanton Barracks, Derby |

From Derby, Harold Cornwell was sent to Rugeley Camp on Cannock Chase to begin his basic training with 6th Training Reserve Battalion, which would become the 6th (Young Soldier) Battalion soon after he joined it. Within a week of his call-up, Harold Cornwell was admitted to Cannock Chase Military Hospital for two weeks suffering from dyspepsia.

He was transferred to 277th (Graduated) Battalion on 18th August 1917 and stayed with this battalion until he was sent to France, although the battalion was redesignated as 52nd (Graduated) Battalion, the West Yorkshire Regiment in October 1917.

|

| Part of Cannock Chase Military Hospital |

Two days after his nineteenth birthday, Harold Cornwell left the Graduated Battalion to travel to Folkestone before sailing to Boulogne, landing on 1st April 1918, and travelling to Etaples the following day to join E Infantry Base Depot, where he would complete his infantry training. Training regimes at the Infantry Base Depots were known to be arduous and sometimes, unnecessarily harsh, and so it may have been with some relief that after only a week and a half, Harold Cornwell was included in a drafting order of men to be posted to the 8th (Leeds Rifles) Battalion of the West Yorkshire Regiment.

The 8th Leeds Rifles had only existed in its current designation since 1st February when 1/8th Leeds Rifles from 49th (West Riding) Division was absorbed by 2/8th Leeds Rifles of 62nd (West Riding) Division. The new battalion had been in action near Achiet-le-Petit during March 1918 as it fought to slow the advancing Germans who had launched their great Spring Offensive, and had lost more than 300 men, including the Commanding Officer, Lt Col Archibald Hugh James DSO*, who died on 26th March 1918. Harold Cornwell was one of more than 360 other ranks to be posted to the battalion during April to bring it back up to strength. Despite having lost about 30% of the battalion’s strength, the battalion diarist did not consider that the battalion’s losses had been excessively heavy, given the circumstances of the fighting.

The battalion was out of the line in Corps Reserve when Harold Cornwell and his draft of men joined it on 26th April 1918 at Louvencourt, where it had arrived from Ablainzevelle the previous day. The men were distributed among the battalion’s companies the day after they arrived.

|

| Lt Col OCS Watson VC DSO |

While in Corps Reserve, the battalion was engaged in a training programme at company level which focussed heavily on raising the standard of marksmanship with the battalion. The training culminated on 11th May 1918 in a brigade strength exercise and a visit from Major General Walter Braithwaite, the division’s General Officer Commanding, who read out a special order of the day detailing the actions of Lt Col Oliver Watson DSO at Rossignol Wood on 28th March 1918 in which he covered the withdrawal of his men in the face of overwhelming numbers of the enemy. Lt Col Watson had led two platoons forward to attack the enemy, who were using two derelict tanks as strong points. Watson’s men were unable to clear the Germans from the tanks and were heavily outnumbered, and he was forced to order his troops to retire. On reaching a position in a communication trench which he thought would be suitable, he ordered his men to continue to the rear, while he remained to cover their escape, even though he was armed only with a revolver, and since suffering serious wounds the previous year at Bullecourt, he only had the use of one arm. Despite the odds and knowing that his decision to stay behind while his men withdrew would almost certainly get him killed, he remained to resist the German advance. And he was killed.

Lieutenant Colonel Watson received a posthumous Victoria Cross for his courage, his self-sacrifice, and his devotion to his men. It was the first of four Victoria Crosses that would be awarded to men of the 62nd (West Riding) Division.

Following the General’s address, the battalion took part in sports on the battalion parade ground.

On 12th May 1918 Rifleman Cornwell reported sick to the regimental medical officer. He was diagnosed with Pyrexia of Unknown Origin and sent off to 2/1st West Riding Field Ambulance at Marieux. Pyrexia of Unknown Origin (PUO) was commonly known as Trench Fever. The illness was caused by the introduction into the body of bacteria found in contaminated earth, most usually through broken skin. PUO was initially thought to be caused by the bites of lice which were a constant annoyance to the men. It was later found that lice were not the carriers of the bacteria, but their crawling over the skin of the men, and their bites, irritated the skin, causing the men to scratch. In scratching their bodies with dirty fingernails, the men introduced the bacteria which caused the fever.

With rest, and a clean set of uniform, and good personal hygiene, most men made a full recovery from trench fever and could quickly return to their units. A minority of men suffered extreme reactions to the bacteria as their bodies tried to eradicate the bacteria. Those men took much longer to recover, or in severe cases, they could suffer permanent damage to joints and their respiratory organs, causing debility and chronic fatigue.

|

| French and British soldiers and German prisoners having their wounds dressed by nurses at No. 29 Casualty Clearing Station at Gezaincourt, 27 April 1918. © IWM Q 8735 |

The Field Ambulance was not intended to admit and treat men with sickness. It’s role was primarily to treat wounds, and to operate as a triage station, transferring men to the receiving Casualty Clearing Station (CCS), which was a larger, semi-permanent medical unit, usually one of three attached to a division, taking admissions in rotation. Here, as the name suggests, men admitted to the CCS who needed to be, would be sent further back to the large base hospitals which had been created in clusters along the northern French coast, where they would either be treated and returned to their unit, or if required, they would be evacuated back to England from one of the nearby ports. Harold Cornwell was sent from the Field Ambulance at Marieux to 29 CCS at Gézaincourt, almost six miles away, where he was one of 124 other ranks to be admitted sick that day. On 13th May 1918, he was sent by Ambulance Train to Le Treport, and from the station there, by motor ambulance convoy to 16 General Hospital, housed in the Hotel Trianon, high on the cliffs on the opposite side of town. The hospital had been established by the British Army in February 1915, but in July 1917 command of it passed to the United States Army and it was re-designated as 16 (Philadelphia, USA) General Hospital.

|

| The Trianon Hotel above Le Treport, where 16 General Hospital was established |

After a week in the hospital at Le Treport, and despite the rest, clean environment, and fresh sea air, Harold Cornwell’s illness had not improved. The decision was taken to evacuate him back to England, and on 21st May 1918 he was admitted to the Kitchener Hospital in Brighton. Brighton had become the hospital centre in England for Indian troops during the early days of the war, but at the end of 1915 the Indian Corps was transferred from the Western Front to Mesopotamia, and the Indian troops were replaced by British wounded and sick. The Brighton Workhouse was taken over as the Brighton Kitchener Indian Hospital, but by 1918 when Harold Cornwell arrived, the ‘Indian’ in its title had largely been dropped. The building is still in use as Brighton General Hospital. A little over five weeks after arriving in Brighton, Harold Cornwell had recovered enough to be transferred out of a proper hospital setting into a convalescent hospital at Woldingham in Surrey, very close to the garrison town of Caterham, where he would remain until 27th September 1918 while he underwent a rehabilitation programme of physical training to help him regain his strength and fitness.

Following his release from hospital in the south of England, Harold Cornwell was transferred to 3rd (Reserve) Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment. The transfer took place on 5th October 1918, but he didn’t join his new battalion until 15th October, so it seems likely that he was granted a period of leave to bridge the hiatus between leaving Woldingham and travelling to Whitley Bay, where his new battalion was stationed.

Even though Harold Cornwell had been discharged from hospital, he was still not fit for front-line service. The description of his condition points to him having suffered a degree of permanent damage to his lungs and his joints. As a member of a reserve battalion, he would be liable to attend regular medical boards to assess his fitness. If he improved, he could be sent back to the war, but if he deteriorated, he might be selected for discharge. Given that he joined the battalion on 15th October, it is likely that he only attended one medical board while he was at Whitley Bay, because on 11th December, he was admitted to 2nd London General Hospital after contracting ‘flu in the second wave of the epidemic that swept the world during 1918 and 1919, with the final throes of it dying out in 1920. His compromised respiratory system made him particularly vulnerable to the ‘flu, and he spent a total of 62 days in hospital while he recovered.

On his final release from hospital on 11th February 1919, Harold Cornwell was no longer fit for any kind of military service, and arrangements were made to discharge him from the army. He left on 15th March 1919. In the wake of his discharge, Harold Cornwell was awarded a Silver War Badge, a wearable emblem to signify that he had been discharged from military service due to ill health. He was also assessed for a disablement pension in respect of the trench fever that had caused his discharge. Initially, he was awarded a pension of five shillings and sixpence per week for his 20% disability. His condition would be reviewed again in a year.

|

| A Silver War Badge, awarded to discharged service personnel to wear in civilian attire |

Harold Cornwell returned to his family home at 1 All Saints’ Street, in the Radford area of Nottingham. His father, Thomas Cornwell, was a well-known journalist in the city, who in the more than twenty years he had lived there since moving from his native Preston in Lancashire, had gained respect as an agricultural and sporting journalist working on the Nottingham Evening Post and the Nottingham Guardian. The house, on the corner of All Saints’ Street and Tennyson Street was also home to his mother, Florence, his sisters, Rose, Florence and Dorothy, all of whom were older than he was, and his younger brother, Edward.

|

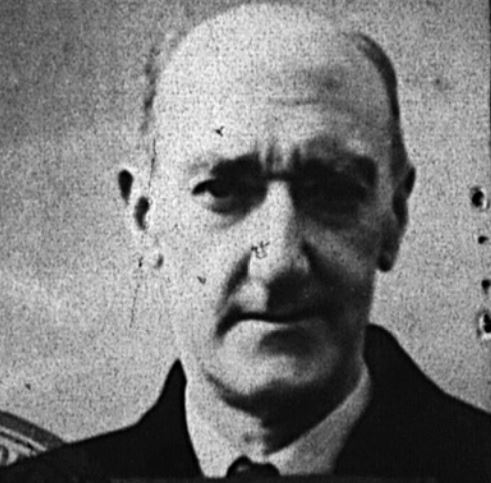

| Harold Cornwell aged 21 when going to sea for the first time in 1920 |

Surveying equipment in the early twentieth century was bulky and heavy to carry, and as one of the main complaints of Harold Cornwell’s trench fever was that it had left him with a weakened and painful back, he may not have been physically able to continue to complete his interrupted apprenticeship. Instead, he joined the Post Office in 1919 and trained as a wireless operator. He gained his Postmaster General’s Radio Certificate in 1920 and went to sea with the Blue Funnel Line aboard the company’s cargo ship SS Teucer as a wireless operator in September 1920. It was the beginning of a career with the Merchant Navy that would last for more than thirty years, with service in at least twenty-five vessels. Most of the ships Harold Cornwell sailed in were the freighters and cargo ships that formed the backbone of British global trade.

|

| SS Tuecer on which Harold Cornwell went to sea for the first time as a wireless operator |

Harold Cornwell continued to sail in the Merchant Navy during the Second World War, participating in many Atlantic convoys. He also crossed the Pacific and Indian Oceans several times, and while it is known that most of the ships he had sailed in prior to the war were lost during it due to enemy action, there is no record of any ship in which he was serving having been sunk while he was aboard.

|

| Harold Cornwell's Medals |

At the age of 53, Harold Cornwell was forced to retire from going to sea due to rapidly deteriorating health, and as SS Rutland docked, he was discharged for the final time. A single man, Harold Cornwell returned home to Nottingham to live with his remaining family. His youngest sister, Dorothy, had died suddenly in Skegness in 1928, his father had died in 1941, and his mother in 1945. Harold Cornwell was away from home when each of the deaths occurred. None of his siblings had married, and they all lived together at 26 Baker Street in Radford.

|

| Harold Cornwell, pictured on his Final Discharge Certificate from the Merchant Navy |

Harold Frederick Francis Cornwell died on 16th December 1952 at the Sherwood Hospital in Nottingham. He was buried three days later in Church Cemetery (also known as Rock Cemetery), close to his Baker Street home. In time, sisters Florence and Rose would be buried with him.

|

| Harold Cornwell's grave in Church (or The Rock) Cemetery, Nottingham, which is shared with two of his sisters. |

Comments

Post a Comment